|

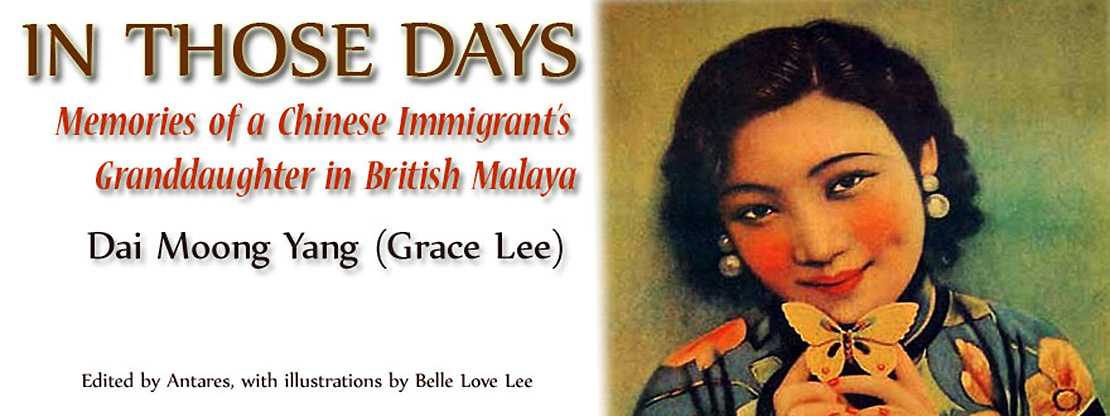

| Siew Sum Chee (the author's mother) at age 18, before she left Hong Kong for Malaya |

A BIG CROWD was gathered outside the community hall of a Hakka village. People were jostling to see what was going on inside. Someone had intruded on the Council of Elders while they were in a session, deliberating the affairs of the village. Who was it? Who would dare? What was the trouble? Must be something serious.

Inside the community hall there was an astonished hush. The venerable members of the Council were granting an audience to a girl of twelve! Those who were lucky enough to have a view of the proceedings could only gape and gawk at the temerity of this rosy-cheeked child.

Her name was Siew Sum Chee. And she had marched in boldly on the Council Meeting to lodge a formal report against her seventh uncle. He had been making arrangements to have her sold as a child bride, thinking he could profit thereby from being her guardian. There was no one else she could turn to for help. Her widowed mother was meek and indebted to the uncle, and her only brother was ten years old.

True, she had many other uncles – nine in all – but none had ever bothered to send money or even keep in touch. One was a hotelier in Hong Kong, another had migrated to Malaya and was a tin miner in Seremban. The others she hardly knew. Her own father had had little contact with them, and he had died when she was ten. Her mother had been trying to support her two children by taking on odd jobs. Sometimes she worked in the fields. She also hired herself out as a professional mourner, paid to swell the numbers at wakes and funerals; she could wail on command.

Bereavement, it seemed, was the recurring refrain in the family’s fortunes. Siew Sum Chee’s mother had been born in bereavement: her mother, married scarcely a year, had not survived her first child. She had died in agony on a wooden pallet, victim of a well-meaning but heavy-handed midwife, who had practically sat on her to force her contractions. As a result, Siew Sum Chee’s mother was raised on bananas, her father being too poor to employ a wet nurse.

Wet nurses in those days were a luxury only the rich could afford. Dainty concubines with bound feet who hardly walked or did physical work were often too frail to nurse their own babies; and, besides, breastfeeding was such a vulgar, uncomfortable routine, fit only for peasant women. Thus it was not uncommon that the children of the wealthy grew fat on peasant women’s milk. As for the children of the poor mothers who had to serve as wet nurses… well, they had to be content with rice gruel or sweet potato – or bananas (which, as we now know, are a good source of glucose and potassium). At any rate, Siew Sum Chee’s mother had thrived on her milkless diet. She was in fact strong and healthy all her four score years.

As a child, Siew Sum Chee’s mother had to earn her keep tending cows, and as soon as she came of age the family married her off to a tailor: a frail-looking widower who seemed a good catch; so what if he had two grown children. Soon, a daughter arrived, then a son, and within a decade the tailor had died, leaving his serious-minded and rosy-cheeked young daughter in her present predicament.

THE COUNCIL OF ELDERS listened gravely to Siew Sum Chee’s complaint, impressed by her eloquence and strength of spirit. One member in particular was deeply moved by her obvious intelligence, her courage and the luminous quality of her beauty.

“Now, here’s a child that deserves a better chance in life,” he thought. It so happened that he had returned to the village on one of his sporadic visits and had decided to sit in on the Council Meeting. He was a cultured, liberal-minded Christian of some means, and he now resided in the big city.

His name was Mr. Zane. (At least, I think it was, for I never heard it mentioned till long after Mama’s death, when he sent us all an invitation to visit him in Hong Kong. But we couldn’t go, and he moved to Hawaii, and we completely lost touch… but I’m getting ahead of the story.) There and then, Mr. Zane decided to adopt Siew Sum Chee as his foster daughter.

He would send her to a Methodist boarding school in Hong Kong. Her mother could visit her at school any time she wanted.

And visit she did, fairly regularly – squeezing out of her the pocket money that Mr. Zane sent without fail. But we must understand that Grandma Siew had experienced nothing but hardship her whole life. (Feeding on overripe bananas had turned her into a bit of a bloodsucker.) Meanwhile, the apple of her eye – her only son – had been recruited to work in his uncle’s hotel. It didn’t take long for him to corrupted by the sleazy company he kept in Hong Kong’s red light district. After all, he was in his impressionable teens.

MAMA PROVED to be a brilliant student. Among the numerous prizes she won was a beautifully lacquered box, which is now in my possession. When she had completed her secondary education, her benefactor and foster father broke the good news: he was going to send her and his only son Andrew to Shanghai for further studies.

Mama was overjoyed and excited, for it was a very rare privilege for a girl to receive such a fine education. Grandma Siew broke down and wept bitterly. She had waited so long for her daughter to finish school and get a good job, so that she could help with her younger brother’s education. All these years she had dreamed of the day when her children could support her in comfort; how many more years did she have left, to enjoy life just a little?

Mama thought about it for a long time and then she wrote a letter to Mr. Zane, explaining why she couldn’t accept his generous offer. She was profoundly grateful for his kindness, which she hoped someday to reciprocate.

The day never came, even though her foster father lived over fourscore and ten years, for Mama died in her thirties. Three months after her funeral, I opened a letter addressed to her. It was from Mr. Zane, with many photos of his family and a warm invitation for all of us to visit him. It was one of the saddest moments I can recall. Would Mama have gone to stay with her foster family in Hong Kong and taken us with her? Might she not have been alive now? If only Mr. Zane had written earlier… if only… if. Fate doesn’t allow any ifs to alter our lives, does it?

Mr. Zane understood Mama’s dilemma, bless his saintly soul. Not only did he readily release her from any obligation to him, he continued sending her beautiful clothes down the years. He must have spoken of her a great deal at home, for his son Andrew (whom we called Brother Fong) made attempts to trace our whereabouts after they had settled down in Hawaii. In 1965, Andrew’s widow instructed her grandson to look me up when his ship docked at Port Klang. Alas, I wasn’t home when he came knocking on the door. Our families seem destined not to meet – even unto the third generation!

GRANDMA SIEW had a long-range scheme. She would move to Malaya with her two children and look for their ninth uncle in Seremban. He was a prosperous tin miner and a bachelor. (It was known that he had a mistress and that she had adopted two children, but they had no legal claim to his fortune.) As their blood relative, he would be obliged to extend hospitality, which they would gratefully accept. In due course they would be included in his will.

Mama thought it was one way the family could stick together, and agreed to the move. Furthermore she had heard that the cost of living was much lower in Malaya; she could easily support the family on a school teacher’s salary.

Ninth Uncle happened to be a staunch Roman Catholic – a fact Mama learnt after she had arrived in Seremban with Grandma Siew and her brother. And, to Mama’s horror, Ninth Uncle revealed that he had made plans for her to enter a convent. In those days, sacrificing a child to the Church brought great honour to a family, and Ninth Uncle had long hungered for such an honour.

While she was at boarding school in Hong Kong, Mama had become a hardcore Methodist. But she bore no religious prejudices. She had never forgotten that it was her Buddhist neighbour who had hidden her from an anti-Christian pogrom during the Boxer Rebellion; she was only four then and her mother had been out earning a living.

So Mama went quietly to the convent and stayed there for several months – until she found an opportunity to slip out and escape to Kuala Lumpur, where she was offered a job teaching Chinese to the Chinese students at the Methodist Girls’ School. Miss Marsh, the principal, took an immediate liking to Mama, but could only pay her twenty dollars a month.

When word of Mama’s absconding from the convent reached Ninth Uncle’s ears, he promptly threw out Grandma Siew and her useless son. Now Mama had to provide for three mouths in a rented room on twenty dollars a month. Tough going for a seventeen-year-old!

Even today there are Chinese mothers who would not regard it as unjust to sacrifice their daughters’ happiness for their sons’ welfare. In some homes it is customary for the parents and the menfolk to sit down at table first; the women have the remnants. This is especially true in the villages, the reasoning being that the menfolk, as basic providers, had to work harder than women. Exceptions are granted in the case of expectant mothers, who are allowed a few extras. I remember my cook’s comment as she was dividing an apple between my own children: “Your son must have the bigger half since he will have to work harder when he grows up!” I know who works harder now.

IT WAS AT THIS DIFFICULT TIME that Siew Sum Chee became aware of the attentions of a very presentable bilingual young choir member, who never failed to attend church services with a big fat bible under his arm.

He told Mama he was a Baba, born in the Straits Settlements, and she believed him, of course. Being new to this country, she was unaware that most bona fide Babas and Nyonyas don’t even speak Chinese – what more quote the classics!

Now, why on earth would Mr. Dai, the bible-toting, poetry-loving Court Interpreter, lie to Miss Siew, the conscientious school teacher, about his cultural background? He had fallen in love with her, you see, and badly wanted to marry her. And when a girl agrees to marry a man, she is actually agreeing to marry his entire clan – to be at the beck and call of the mother-in-law, the elder sisters-in-law, even the grandmother-in-law. A good wife was supposed to obey not only her husband, but everybody else in the family who happened to be senior to her in years.

In my own teens, I was given a lot of advice about how to select a mate. Stay clear of Hakka men, they’re all wife-beaters. Hokkiens are tight-fisted, and Teochews are no better. Hainanese men all end up as cooks and butlers in European households. Foochows are slothful and will even pawn their wives when they’re broke. Cantonese men, however, pamper their wives, and if they can afford it they will hire domestics to relieve their wives of hard work (that’s why Cantonese women are such notorious mahjong addicts). There’s only one snag marrying a Cantonese; he’ll become polygamous as soon as he prospers. True, polygamy observes no dialect boundaries, but there is a difference: the others will make their concubines work like servants.

The best choice would be a Baba. They’re fun-loving and easy-going, and don’t believe in disciplining their wives too much. In fact, they often let their mothers-in-law run the household. Babas like to sing and dance and enjoy a leisurely lifestyle. Their Nyonyas play chip ji kee all day and chew betelnut and decorate themselves with gold and precious stones.

“We Babas have no qualms about living with in-laws,” Mr. Dai told Miss Siew. “If your dear mother and brother don’t mind, they are more than welcome to live with us when we are married.”

But it was the love letters from Papa that Mama liked best. She was swept off her feet by his poetic soul and his mastery of brush and ink. At her age, how was she to know that husbands are not in the habit of writing love letters to their own wives?

MARITAL BLISS would have been Mama’s to enjoy, were it not for her dear husband’s flirtatious nature. He would be out on the town, dandified and perfumed, while she was housebound and heavy with child.

It was a small blessing that my father’s parents had their own house, so Mama was spared undue interference from her parents-in-law. Grandmother Dai, however, was fond of visiting Mama and baring her soul to her. The poor woman looked so underfed, living with a miserly husband, that Mama always made sure she ate well on these visits. Over the years the two grew quite attached to each other, and I believe Mama loved her mother-in-law more than her own mother, whose scheming and money-grubbing had brought such heartache.

Mama spoke a little English and several Chinese dialects, and played the organ fairly well (though she stuck strictly to hymns). Papa’s musical instrument was the accordion, and he had to keep buying new ones because of my penchant for sticking my little fingers into all the delicate parts. He never punished his children. Once he built a wooden fence around his workdesk to stop me from rummaging through and destroying his things. I continued in my mischief till my parents put me in St. Mary’s boarding school at the age of eleven, so that I could learn some ladylike ways. It must have been quite an expense for them, for I don’t recall Mama buying nice clothes for herself from then onwards.

BEING A GOVERNMENT SERVANT, Papa was transferred all over the Federated Malay States, serving as interpreter in courts of all sizes, in both urban and rural settings. My parents were married in Kuala Lumpur, but I was born in Tampin, Negri Sembilan, in 1916. We then lived in Sitiawan until I was six, at which time we moved to Kuala Lumpur. After a time, Papa was transferred to Temerloh, in Pahang. The only way we children could get a solid education was for him to send us all to a boarding school.

The arduous car journey between Kuala Lumpur and Temerloh became a regular event, and it took a toll on Mama’s health – especially since she was pregnant again. In those days, the roads cutting across the Main Range were hazardous: oftentimes at dusk you could see tigers cavorting with their cubs in the middle of the road.

Wild buffalo and sleek black seladang would graze noisily around and under our house in Temerloh, which was raised high on concrete stilts. Hornbills over a foot tall would fly into our bedrooms when they thought no one was about. Larcenous monkeys would slip in through the kitchen window in search of fruits or anything edible. Centipedes and scorpions were often crushed underfoot by anyone brave enough to visit the toilet at night; you could hardly see them in the faint glow of your kerosene lamp! At the same time, you could hear all the night noises of the dark jungle, which started only a few feet behind our government quarters. And besides all this, it was mosquito country, to be sure.

To the typical Chinese civil servant, therefore, a posting in Pahang was tantamount to punishment. Everyone without exception would pray for a reprieve, which meant a return to “civilization.” Papa’s Indian friends, however, appeared to relish living in the boondocks. They reared cattle, kept vegetable plots, and ordered around a huge army of labourers. Out here, it was easy to find cheap labour, and even an ordinary government servant could afford two or three domestics, cowherds, gardeners, and perhaps a male cook. Best of all, there were no temptations; no eyecatching window displays in the shops, no pubs or nightclubs, sometimes not even a cinema. It was easy to save money, but no self-respecting Chinese cook or amah would look at it this way. “Very sorry,” they would say, turning down an offer of higher wages, “no one can live in such primitive surroundings!”

MAMA HAD TAUGHT HERSELF Mandarin, and was now giving us lessons in this nationalistic new lingua franca, which was being heavily promoted in China to unite the myriad dialect groups. It was around this time that the cheongsam (“long dress”) came into fashion, though the Northerners insisted on calling it the cheepow. Ours were quite modest, with elbow-length sleeves and hems just below the knees. Well-behaved girls wore their cheongsams loose, but “loose” girls wiggled about in tight-fitting ones, with high slits to reveal the maximum amount of porcelain-smooth thighs. Before the cheongsam came along, I was wearing Chinese blouses trimmed with embroidered ribbon, mid-length skirts, and pointed shoes with silk or cotton stockings.

Mama used to carry either a tiger-skin or beaded handbag. She wore no jewelry apart from a pair of tiny pearl ear-studs (to conceal her ear-piercings, she said, because they were so ugly; we never had our ears pierced while she lived). While other girls flaunted gold trinkets, we wore only a thin gold chain and a watch. Mama regarded chains on wrists and ankles as symbols of slavery. Pierced ears, according to her, weren’t only unsightly; they were primitive and barbaric.

I WAS ALMOST FOURTEEN, in 1930, when Papa was transferred to the Education Department in Kuala Lumpur, to be an Inspector of Chinese Schools. For a while, we were a happy, reunited family living amidst lush greenery in the vicinity of Imbi Road, Kuala Lumpur. Then we began to notice that Mama’s eyes were puffy from extended bouts of weeping. We knew that Mama’s sorrow had something to do with Papa.

While on his rounds inspecting Chinese schools, Papa had discovered that the headmistress of one of the girls’ schools was a relative – some species of cousin. (We later nicknamed her “Guy,” after Guy Fawkes, the man who nearly succeeded in blowing up the British Parliament.) She was either widowed or divorced, thirty-five years old, abrasive-tongued, repulsive-looking, and compulsively predatory. She pounced almost immediately.

Papa was easy prey. Those who knew his taste were incredulous and surprised. Mama wasn’t. These were lean years for everybody, and beautiful women weren’t going for free. Besides, he wasn’t enjoying his new job in the Education Department as the government snoop, going around the Chinese schools sniffing for Communist ideology.

Chinese school teachers in those days were all graduates from China, but they were paid no better than salesmen or clerks. They were subjected to all kinds of injustice: their degrees weren’t recognized and they were generally made to feel inferior to those teaching in English-medium schools. They were even paid less for private tuition than their English-educated counterparts. With all their fine degrees and years of experience, they could only afford to live in cubicles while trying to make ends meet. Meanwhile, their illiterate countrymen were raking in the chips and returning to China as millionaire heroes. Little wonder then that the Chinese schools were a breeding ground for Marxist philosophy. Mama herself was paid the princely sum of $1.50 per child per month for teaching them six days a week, privately – and their children kept borrowing our textbooks, much to our annoyance!

OVER THE YEARS, Mama had told us about the kind man who had rescued her from an arranged marriage when she was twelve. She said he still wrote to her, asking her to visit him in Hong Kong. She said he was like a father to her, and he was keen to meet our family. During those dark days – the days of Guy – I suggested to Mama that we accept her foster father’s invitation and move to Hong Kong. Loy and I could find work there; after all, we were about to sit for our Senior Cambridge Examination. We could start life anew in Hong Kong! It sounded rather exciting. To us, Hong Kong was as wonderful a prospect as England or America (I hadn’t even heard of Australia). Surely her generous foster father could help with our passage? We’d leave Papa behind to have his endless affairs. (I was only sixteen then, and knew nothing of loyalty or faithfulness. And I was never close to my father who, like most Asian fathers, hardly ever communicated seriously with his children.)

Mama had been pregnant six times. Two boys were stillborn and a girl miscarried, leaving her three precious daughters – Moong Yang, Moong Loy and Moong Wai.

Guy (I never addressed her by her real name, such was the hostility I felt towards her) had the gall to come to our house and taunt my mother, pointing out that it was traditional for a woman with no sons to vacate her wifely position in order that her husband could remarry and have male heirs.

Mama believed in tradition, even though she was a rebel at heart. In an attempt to produce a son, she conceived again, but in her fallopian tube. She developed an infection after undergoing a hysterectomy. Antibiotics were not in use in those days, and Mama never left the hospital alive. She died in December 1933, at the age of thirty-eight.

AFTER MAMA’S DEATH, we had to move house because Guy couldn’t stomach staying in the Imbi area with all our old neighbours around. Years later, I learned that Papa had married her under threat. He must have thought she was capable of extracting vengeance by poisoning us all. It was no joke. I believe she would have done it too, the wicked witch! Anyway, she got a good dose of her own bitter medicine when Papa married a girl of eighteen.

Mama had warned Guy of Papa’s infidelity. He could never be faithful to any woman, just as a leopard can’t change his spots. But Guy had been confident of her power to control him.

Well, Papa met his third wife at one of his regular mahjong sessions. She was a refugee from Kwangtung, staying at her stepsister’s house in Kuala Lumpur. A goodnatured and cheerful soul, she was six years younger than I, the eldest daughter from his first marriage, and she bore him four more daughters and two sons.

Papa died in 1969, aged seventy-four. My third mother died in 1992, aged seventy-one. I don’t remember when Guy died. After all these decades, I still find it hard to think kindly of her.

But I’m sure my mother Siew Sum Chee has forgiven her, the angel that Mama was, and shall always be to me.